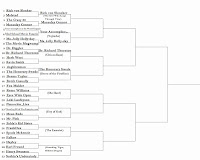

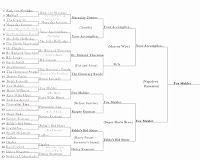

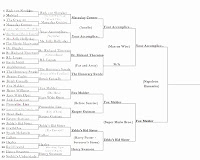

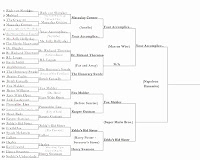

Ouch. That last battle had a pretty clear winner from early on. And with that, The Honorary Swede moves on to Round 2! For this next battle, we get the second animated flick of the tournament–Disney classic, The Little Mermaid. Read, vote, comment, enjoy! You have until Tuesday. NOTE: I totally revamped the bracket. I retyped the names to make them easier to read, changed a few nicknames (either contestant switches or requested minor name alteration), and added the list of movies to be reviewed in Round 2! So below is the updated bracket. Click to make it bigger.

———————-

Review #1

By Deems Taylor

I haven’t watched The Little Mermaid since I was a child. Even then, I didn’t care for it. I’d always fast forward through the film to get to the parts where Scuttle, a seagull voiced by the hilarious Buddy Hackett, would share his worldly opinions or help set the mood. I’ve grown up since then and figured I’d be able to watch the whole movie without fast forwarding. It was tough, but I was able to make it through and I realized I still didn’t care for the now over twenty year-old “Disney Classic.”

We all know the story. Prince Ariel wants to be part of the human world but her father, King Triton, forbids it. Ariel doesn’t listen and after rescuing Prince Eric from a horrific sea storm, she ends up making a deal with Ursula (my newly crowned second favorite Disney villain) to become human. But there’s a catch, and there is ALWAYS a catch, because Ariel doesn’t have her voice. Using her wit and charm she must win over Prince Eric and share a true loves kiss or else Ursula gets Ariel. But of course, SPOILER ALERT, true love wins out and Ariel sails off into the open sea with Prince Eric as a Disney chorus takes us out. Roll credits.

As a child, I would fast forward through the main story because I didn’t want to hear Ariel whining or watch Flounder as he continuously screws up situations. I would also fast forward through most musical numbers because they dealt with love or were annoying. But as an adult, paying full attention with Yoo-Hoo by my side, I discovered that as I got older, I made a great decision as a child. The film is filled with sea-pun laden dialogue and a story that should have never happened in the first place. Within the first twenty or so minutes, the audience discovers that Ariel is sixteen years-old. All King Triton had to do was say you’re punished, go to your room and the story was done. But no, Ariel had to complain how life is hard being a teenager and that her father doesn’t understand her. She disobeys him, goes to the surface rescues Prince Eric and when confronted by her father, Ariel breaks and exclaims she loves him. Ariel knows NOTHING about this guy other than he’s a good-looking Prince with a goofy dog. When she makes the deal with Ursula, she becomes human, but as payment she must give up her voice. Oh, and she has three days to fall in love with Prince Eric using only her sixteen year old body. At the end of the film, it’s maybe a week since she first saw Prince Eric and they are married and sailing off to the sunset. What frustrated me even more was how okay King Triton was at the end of everything when the entire time he talks about how much he detests humans. If this was a live-action film, it would have been panned on plot and dialog alone.

But lame dialogue, major plot issues, and Flounder aside, the film does have some positives. Scuttle. The second Scuttle came onto the screen, I was howling with laughter. It reminded me how much joy and humor I find in vaudevillian, slapstick, and sight gags. My inner child came out to watch Scuttle explain what a dinglehopper or snorfblat is and laughed harder every time he would come onto the screen. Sebastian, the crab, was great for all musical numbers he was involved with. Adding his vibrant colors and energy to any number he’s involved with be it a musical celebration of sea life, helping Prince Eric to kiss the girl, or running for his life Tom and Jerry-style from a crazed chef who may/ may not be French or an offensive French off-set. Then there is Ursula, the delightful Disney villain who seems to be having fun no matter what she is doing. Her musical number is solid and she’s modeled after legendary John Waters character Divine for goodness sakes. Who wouldn’t be having a grand time looking like that?

In the end it comes down to this: children will enjoy the film for its colorful musical sequences and humor while adults will want to fast forward. Try another Disney film if you’re looking for something that appeals to all ages.

–Deems Taylor

———————-

Review #2

By Botch Casually

The Little Mermaid is likely best known today as the picture that launched the Disney Renaissance, marking a return to form for the studio of a certain level of charm and brio. Following the deaths of co-founders Walt and Roy Disney in the ’60s and ’70s, the company had spent years wandering the deserts of mediocrity. After The Little Mermaid would come Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin, The Lion King, and many others through the ’90s, most of them massive moneymakers. It may be tempting to locate the start of any such renaissance back one year, to the studio’s collaboration with Steven Spielberg in 1988 on Who Framed Roger Rabbit. In many ways, that’s the picture that restored interest among mainstream audiences in feature-length animated entertainment (or semi-animated, as it mixes live action with the cartoons). But Roger Rabbit, for all its many impressive virtues, is hardly in the Disney style.

That would be the job of The Little Mermaid. No doubt there are volumes of behind-the-scenes corporate backstory to this movie, involving industry players, gutsy business calls, and various career-making and -breaking maneuvers. It’s also easy enough to pick out various elements and call “formula”—yet another princess story based on yet another Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale, yet another musical, and, as always, damnably cute more than 70% of the time. But in the end that’s incidental to what ended up on the screen. In the watching, The Little Mermaid is one of those happy accidents where all pieces fall together and the result is something close to an ideal, achieved seemingly effortlessly.

Even for those less than dedicated followers of the studio, such as myself (herewith exposed to The Little Mermaid for the first time, which by the way is scheduled to be rereleased next year in a 3D version), the sheer professionalism of the production tends to make it go down easy. It moves from one intricate set piece to the next with a minimum of fuss, and always gracefully. It has a natural feel for the rhythms and counterpoints of both comedy and romance, playing them off each other expertly, the one always relieving the other as they periodically skirt close to excesses.

It’s a musical, of course, and the one thing no one can deny is Disney’s unique capability of marrying the exuberant fantasies of musicals with the natural expressiveness of animation. Several flat-out big musical production numbers are scattered along the way in the compact 83 minutes of The Little Mermaid, and they also go down easy, with sparkling variety from song to song. Ariel, the 16-year-old little mermaid of the title, is voiced by Jodi Benson, an accomplished singer and stage actress in her own right. One of the comic sidekicks of Ariel is a crab named Sebastian. He is possessed of a Jamaican patois and also holds a position as composer in the court of Ariel’s father, King Triton. Sebastian leads a couple of the best numbers here, including “Under the Sea,” which won an Oscar for Best Original Song (the picture also won an Oscar for Best Original Score) and comes with a decidedly calypso bent.

Another of her sidekicks, a seagull named Scuttle, is voiced by Buddy Hackett, and he’s good, a familiar Disney presence, salting down the proceedings with his classic Vegas stand-up shtick, playing his usual amiable idiot. He gets some good gags right along—a phony expertise on the ways of humans, listening for a heartbeat in the sole of a foot, and so on. These bits come and go quickly in the flow of things, and they are economical about keeping the picture light and frothy.

I particularly appreciate that the filmmakers sharpen the contrasts with unsettling elements. The blundering wrath of King Triton is a fearsome sight to behold, and Ursula, a sea witch and an octopus with the style of a hammy grande dame, is genuinely malevolent, and cruel. What Ursula does to the “mer-people” she comes to own is definitely unpleasant, and so is she. But she’s also bawdy, campy, and a lot of fun. In fact, she’s one of the most indelible characters here. Mixing in a little darkness tends to make the white light brighter—a hallmark of Disney’s stock in trade. Ursula, in that regard, is a classic creation.

I also appreciate that the filmmakers were not unmindful of the varieties of changing roles for women—princess stories had to be a lot easier to make before 1989! But they don’t much duck the issues, instead attacking them head-on. Ariel is a fully empowered feminine figure, capable of a physically difficult rescue on the high seas of the drowning prince (and full-time boy scout) Eric and other feats atypical of most shy and retiring beautiful princesses. Ariel is not a bit shy and retiring, and she is clearly making her own choices every step of the way and taking responsibility for them.

In many ways the picture thus manages to have it both ways, a stunt that is probably harder than we can guess. If Ariel appears to be making conventional choices—beautiful princesses, after all, belong with handsome princes, right?—they are arguably enough radical. I mean, think about this for a second. She effectively chooses to throw over her own species, becoming human rather than remaining one of the “mer-people” she was raised as, separating herself forever from her family and loved ones, a choice that is analogous in its way to extremes of plastic surgery paired with a move to the other side of the planet. It’s almost impossible to understate what a huge decision she makes here. Yet somehow the movie finds a way to gracefully elide such questions. Who wouldn’t want to become human, given the chance? Becoming human is another constant in the Disney universe, here established early and often as one of Ariel’s most enduring desires.

Yes, there is a vacuous Barbie and Ken aspect to the central love story here, with Ariel and the prince Eric appearing largely as anodyne, desexualized, and somewhat wooden cartoon-attractive figures of masculine and feminine regularity. But is there any other way to play it, particularly in a G-rated Disney animated musical feature? I don’t think so. And the filmmakers do find ways to poke fun at the strictures they impose on themselves here even as they assiduously respect them. In one very brief scene, Ariel confronts a life-size statue of the prince. She gazes into the explicitly stone orbs under its brow, and purrs, “It has his eyes!”

The Little Mermaid marches straightway and unsurprisingly to its predictable happily-ever-after conclusion, but it loads up on effective touches large and small that make it memorable and a pleasure to return to: the genial ignorance of human ways (a fork is assumed to be a hair pick, which results in a good sight gag at a dinner table) … the great jaw-snapping sound made by an attacking shark … a terrific electrical storm at sea … Eric’s stone face surviving King Triton’s destruction of the statue … the neat way Ursula is given responsibility for the exposition, foreshadowing the second half of the story … the transference of Ariel’s voice to Ursula … Sebastian’s confrontations with the French chef Louis … the way that Ariel, excited about her ride in a horse-and-buggy carriage, hangs off of it upside down to see the view from that angle—and many, many more. It is altogether a concise little marvel of storytelling with numerous pleasures at every juncture.

——————————–

Now Vote!

Exceedingly well-written review by Mr/Ms? Casually. No contest.

I think it’s quite brave to go against the standard opinion of this movie, especially from someone who chose a Disney-related pseudonym, because he has to work twice as hard to convince people who love the movie that it’s not as good as they think it is. I thought he was making some progress, but didn’t do the job enough, especially when Botch does such a great job praising the movie for its strengths.

I don’t knock Deems for having his opinion, but Botch got my vote.

The first reviewer went into the movie with a preconceived notion that they didn’t like it, so of course they didn’t like it. It is our job as reviewers to go into movies with an open mind. He/She was clearly just reviewing the movie for the sake of the competition. That’s a shame – he/she could have really learned something from watching a movie that they normally wouldn’t.

Ditto. Seriously though, who bashes The Little Mermaid?! Who does that????

People who don’t like the Little Mermaid do that.

I see where you both are coming from, but it sets up an interesting question. Should the first reviewer have hidden that fact? Or is it better to be honest about such misgivings?

Also, going in with an open mind is great in theory, but really hard to do in actual practice. I try, too, and I’m not very good at it.

I think what spoiled me on Deems review is he didn’t take the time to possibly look at it from a child’s perspective and/or from an animation perspective. It truly felt like he expected the same things from a live action films. Botch combined the good with the bad. Still love this movie regardless

I don’t have an issue with Deems not liking The Little Mermaid. Opinions are a good thing in reviews, even if I disagree. I just don’t think the review provided enough support for the claims, especially when compared to the second review. It’s interesting to see such different takes and approaches to a film.

Yeah, I was really fascinated by this match-up when I got both reviews and saw how drastically different they were in opinion. I was curious to see how people would react… now I know.

Casualty does a nice job putting the movie into historical perspective in the Disney canon. His/her analysis of the “princess story” themes and balance of contradictory elements is interesting and developed with lots of supporting examples.

The self-congratulatory aspect of Deems’ review is off-putting.

You won’t find many people who dislike The Litter Mermaid, and I thought Deems was pretty brave to state that he’s one of them. I thought his review was funny.

But seriously, no one mentioned one of the best gags of The Little Mermaid? The giant dick statue on the VHS cover? This is the only VHS tape I haven’t thrown out because that’s still to this day pretty hilarious.

As someone who is decidedly NOT a fan of Disney, I suspect my reaction would be similar to Taylor’s. But I voted for BC because I thought he made a better case.