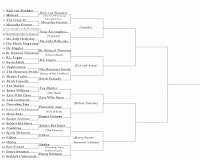

Welcome to Round 2! We now begin pitting winners against each other… and things get much more interesting. For this first battle, we’re looking at a time travel anime, The Girl Who Leapt Through Time. This battle sees Rick von Sloneker, who won his first battle with Speed, against Macaulay Connor, who won his first battle with another animated film… Batman: Mask of the Phantasm. Now it’s up to you who will move forward to Round 3. Read, vote, comment, enjoy! You have until Wednesday. Below is the updated bracket. Click to make it bigger.

——————-

Review #1

By Rick von Sloneker

The Girl Who Leaped Through Time

In 1967 Japanese writer Yasutaka Tsutsui wrote the third novel of his (ultimately) celebrated oeuvre of works. The novel “Toki o Kakeru Shōjo” (or “The Girl Who Leaped/Ran Through Time”) endured as one of his most popular and has adapted multiple times on film, television and theatre. It examined the tale of a middle school girl – Kazuko Yoshiyama – accidental ability to time travel through a time leaping drug. I include this preamble because Mamoru Hosoda’s The Girl Who Leapt Through Time, though oftentimes – erroneously – referred to as an adaptation of Tsutsui’s novel is, in fact, more of a loose sequel. Makoto, the seventeen year old protagonist of this incarnation, is the niece of the original time-leaper of Tsutsui’s imagination. While at school an unfortunate tumble in an empty classroom leads Makoto to discover a walnut-shaped object which in turn leads to a series of shenanigans….

But shenanigans seem to be a de facto part of Makoto’s life – time leaping or no. I’ve observed a curious tendency of anime films where the characters generally exist in a pronounced state of freneticism and it’s all too applicable to Makoto. “In general, I’m quite cautious” she tells us in an early voice-over, but we’re not given any evidence to support this. She wakes up late, wolfs breakfast, arrives late at school unprepared for a pop-quiz, endures a series of pratfalls (one of them whilst discovering that walnut-shaped object) and in a bizarre shift early in the film seems to be hurtling towards her death when….she leaps back in time. So, raise your hands if an experience like that would send you charging to check yourself into the nearest psychiatric ward for evaluation? In real-life we might spend two hours in a precise Von Trier like character study watching Makoto reeling from the implausibility of the experience. However, like so many protagonists in science fiction films, although Makoto is somewhat taken aback by her ability initial she soon accepts it as something par for course. Her aunt Hosoda, the original leaper, (the only persons she betrays the information to) is the one who significantly gives a name to her ability.

It’s a deft trick from the screenwriters. It functions as a dovetail managing to be a sly wink to the original text while explaining away (but not altogether) this bizarre gift. And, at seventeen, and with her penchant for the frenetic Makoto is not too invested in where the gift’s origination. She is content simply using her powers for the mundanities of everyday life – leaping back to pass tests, eat her favourite meal, play karaoke, avoid awkward romantic conversations with a friend – and as the film hurtles past its half way marked its purpose seems assured. The excitable Makoto shall realise that time truly waits for no one and that manoeuvring time for incidental personal gain is only satisfying up to a point. And these things do occur but the how is what intrigues because the film moves from what seems a singular dissertation on coming-of-age machinations to a dissertation on morality amidst a not-quite-fervent love story.

|

| A truly beautiful shot in the film…. |

My Aristotle is just the teensiest bit creaky but the way that the final act reveals how the time-leaping occurs and WHY it occurs reeks so much of his belief that true art should focus not on the mundane but on the truly “important” concepts of life. As a pivotal conversation with a true time-leaper just over the one-hour mark unfolds it seems decidedly at odds vibrant playfulness of the first two thirds as it becomes (but briefly) something more didactic. Of course playful vibrancy can be a tool for learning as much as more obtrusive teaching moments but it’s fluidity from liveliness to philosophy which the film does not quite manage to master. The romantic conceit play truer to form because the way it burgeons from the most innocuous of moments to an almost almost heart-wrenching tale of tragic love is indicative of all the hyperbole which comes with typical teenage life and because it merges with the philosophising of the last half hour its overwrought nature becomes less a crutch which the film must overcome and more of a humorous nod to the way that – when a teen – everything seems to be of life-and-death significance (and, admittedly, Makoto does have life and death issues to deal with). And, the love-story angle becomes the gate-way through which the film ultimately meets its initial goal of allowing Makoto to come-of-age making way for nice reiteration of the film’s rather literal title.

It is the literal leap through time which allows Makoto to make that leap to maturity at the film’s end. And, these are the minor details which underscore the film’s appeal even when at its most unwieldy. Like, the importance of the time-leap precipitant being in the shape of a walnut (when walnuts are mythically a nod to the god Dionysus’ woman Carya who became an oracular tree) or Kazuko (the aunt) working in an art gallery (for what else can manage to outlast time but the permanence of art?) It’s easy to see how these themes might have worked, perhaps more effectively, in novel form but Hosoda attention to detail – in the oddest of places – and the deftness of Satoko Okudera’s screenplay make this a 90 minutes well spent. I suspect that those not inclined to the spiky hairs and reddening faces of anime films might be turned off by the look of the film, but even as the occasional character work is quite broad the animation captures the mistiness of the sun-soaked playfield and the intensity of the clouds (just look at that shot third shot above). Perhaps, not quite a visual triumph but appealing nonetheless. Oh, sure, it fumbles just slightly by not allowing itself to be confident in its own initial playfulness – which the tableau itself visually endorses. And, by doing so it does lose some of its panache but as the film leaps through from plot-point to plot-point, its heart is in the right place, always.

———————

Now Vote!

Here we go!!!!!

Both are very good. Macaulay appears to be a big anime fan and goes a little more in-depth on the film’s history. But I couldn’t get past the frequent use of the first-person perspective, which I just don’t think belongs in movie reviews (or at least should be used more sparingly than this). Point to Rick von Sloneker.

I don’t know… I disagree with the “reviews should not be in first person” thing pretty strongly. Reviews are about your personal experiences and feelings on a film. Not having the option to write in first person seems odd to me. Though we’ve had the personal vs. technical writing discussion a few times already in Round 1. I just personally have nothing against using “I” in a review.

Yeah, perhaps I was a little strong, but there’s a difference between a movie review and, say, a movie journal. One should be as objective as possible, the other, of course, will be critical where appropriate, but can and probably should highlight certain biases held by the writer. First-person writing tends to lack the same authority as something that speaks in a second- or third-person voice.

That said, many of my favorite writers (both professional and non-professional) write first-person film reviews. It comes down to quality, ultimately. Here, the two reviews are close enough that the more objective POV won me over. But Macaulay, like Rick, should be proud of a pretty great piece of film writing.

Both well-written, albeit in need of proof-reading (perhaps I should start hiring myself out). Rick’s review is much more accessible to read, while Macauley’s is ambitious to a fault. I also prefer an objective POV, so perhaps that colored my vote as well.

Interesting how both reviewers note the change in the film’s final third but one is more for it and the other less so. Both are good, but I like the cleverness of the second one.

I find it a bit weird to call definitively for “objectiveness” as an essential for reviews. Since any review or critical piece is basically just a subjective view with points to back up your opinion. But, that’s just me, I guess.

Haha, it’s OK. I agree with your objectiveness comment. That seems odd to me, too. But what do I know?

For me, it’s all about the structure and flow of a review. If a writer speaks from a first-person perspective, it can be great if the writing is well-crafted. The issues appear for me when it becomes so informal that it feels like it was written in 15 minutes. There can be the same issues with a third-person review being too stale or generic. It’s all about choosing a style and doing the best you can at that approach.

For this contest, I think both reviews are good. I gave my vote to Rick Von Sloneker because I felt that it flowed better overall. It was very close, though.

Those reviews were excellent. I wish I could vote for both.

I love how tight this race is. Either reviewer should be justly proud of a win–both reviews are very, very good.

It was a close call, both are very good reviews. But in the end, I thought Rick’s made me want to watch the movie more, and I thought Macauley’s was a little too vocabulary heavy.

I like the personal approach better and it’s nice to learn something from it at the same time, even if it was a big heavy on the words.

and it’s nice to learn something from it at the same time, even if it was a big heavy on the words.

I like Macaulay’s beginning better, and I like Rick’s ending better (despite the Naka Riisa laugh and comedy comment, which I think is part of the Japanese comedy format with the unique laugh and clumsy female lead thing).

So which one did I vote for?