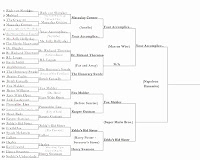

This is it, guys and gals. It’s the last battle for Round 1! I will be posting up all Round 1 Fallen contestants, along with the winner of this battle, on Friday. As for this one, we had yet another last-minute replacement for somebody who had to drop… hopefully this will be the last drop of the tournament! But what a better way to end a behind-the-scenes-issue-filled round than with a Terry Gilliam flick? This time we’re looking at Gilliam’s Brazil. Did we save the best battle for last? You’ll have to let me know! Read, vote, comment, enjoy! You have until Friday. Below is the updated bracket. Click to make it bigger.

———————–

Review #1

By Mean Reds

Brazil is known to be one of the greatest science-fiction films of all time with a unique take on the dystopian genre. Terry Gilliam (Monty Python, 12 Monkeys) co-wrote and directed this film based on the concept of an over-bureaucratic society where the so-called advances are actually just exercises in difficulty and illogical systems.

This story begins with a minor incident—a typo—that leads our lead character Sam Lowry (Jonathon Pryce) into increasingly complex, and even life threatening situations. Lowry works for the Ministry of Information, an institution in this fantasy version of society “somewhere in the 20th century” (and no, it doesn’t take place in Brazil) that controls all of the access of information in society.

Lowry has no wish to advance his career, despite his wealthy mother’s wishes. He does, however, have dreams about a mysterious woman who seems to hold the key to a better life outside of his dreary working existence. His dreams are majestic, fantasy scenes that break up the very gray sequences within the Ministry of Information. He also experiences issues with his duct system that creates further conflict in his life with Central Services, the universal public works institution.

It’s difficult to find a way to summarize Brazil because it functions as film by moving from one seemingly resolvable scenario to even worse obstacles. Lowry finds himself in this predicament because of the Ministry of Information’s ridiculous processes and refusal to admit the smallest error on their part.

I enjoyed this film and think it’s a stunning example of the genre. This isn’t a version completely unlike other dystopian ideas found in Orwell’s 1984 or even some of the visuals in Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange, but Gilliam crafted a unique world of his own. Watching this movie, I was surprised by how Gilliam was able to advance the plot while still focusing on the ludicrous society he’s put to screen.

The level of detail in reflecting the absurdity of the plot into the fabric of the society was exciting to watch. From the futuristic meals (or slop) in a restaurant to the jumble of air ducts hidden behind Lowry’s walls to his malfunctioning breakfast machine, every thing was comical yet thematically serious. What the society deems as better is obviously not and only serves to make things more difficult for its citizens.

The comical set up of police officers making an arrest by cutting a hole in the ceiling and coming down a pole is instantly made sinister with the odd sack strapped around the prisoner. These sort of juxtaposing visuals and set pieces create a rich viewing experience throughout Brazil. It sets up Lowry’s necessity to escape this society with the woman of his dreams (literally), Jill.

What I found fascinating was how relevant this film is today. The contrasting depictions of the upper class, obsessed with cosmetic surgery and control against the lower class that are treated without any sense of decency can easily draw comparisons to the sentiments of Occupy Wall Street. A subplot of the film is that there are currently terrorist bombings taking place, targeting the upper class and government. The actual wanted criminal that escaped incarceration because of the typo, repairman Harry Tuttle (played marvelously by Robert De Niro) is wanted simply for working outside of the bureaucracy, an indicator of suspected terrorism. On an even more basic sense, it’s easy to relate to the burdening and seemingly counterintuitive government procedures and paperwork we deal with on a day to day basis.

I found myself laughing at the nightmarish society put to screen in Brazil but Gilliam’s intent in that is clearly visible. The use of the song “Aquarela do Brasil” (also, the inspiration for the film’s title) throughout the film is sort of perfection and yet another layer of whimsy on top of dark themes and visuals. The spectacular ending sequence truly makes this film remarkable and gave me something to chew on well after viewing. This is a greatly entertaining movie that has something to say, but even more to show. I would suggest watching it as a companion piece to A Clockwork Orange for an even better experience.

————————

Review #2

By Kasper Gutman

I’ve always been fascinated by the work of Terry Gilliam. Like David Lynch, Jean Renoir, and a few other directors, Gilliam is a director who makes auteur theory look like a real thing. Everything goes into the vision of the film, and Gilliam—regardless of any legendary battles with the studio—always shines through in the end product. Brazil is one of his first non-Monty Python efforts, and is legendary in terms of struggles for creative control and vision. Like Blade Runner, there are multiple versions of this film. For this, I watched Gilliam’s Final Cut.

That vaunted vision is best summed up as George Orwell’s “1984” on hallucinogenic drugs with a side order of Kafka. The film portrays society as a logical fallacy in which only the insane can survive and the only escape is through fantasy. Sam Lowry (Jonathan Pryce) is a low-level bureaucrat who exists in the real world only because he has to, and retreats into a fantasy world at every opportunity. This fantasy dreamland features Sam encased in shining silver armor and equipped with wings allowing him to fly into the pink-tinged clouds.

This is contrasted with his real world, a drab nightmare of files and gray little men. Sam works in the Records Department of the government, and it’s soon evident that the bulk of the workforce is, in fact, employed by the government in some capacity. Everything is bureaucracy and suspicion. Everything is done only with the proper application of the proper form. It has the appearance of (at least to the many involved in the upper levels of the hierarchy) working properly, but of course is a true nightmare. Things are done one way simply because they are done that way, and the entire society revolves along rigid adherence to “the rules.” These rules, certainly written down within the society in endless codices and codebooks, exist to regulate every aspect of existence, and mistakes do not happen. When they do, they simply don’t, and correcting any mistake leads to an endless bureaucratic loop. Mistakes do not happen.

Naturally, the film opens with just such a mistake. A man named Archibald Tuttle (Robert De Niro) is sought by the government for unknown reasons. As the forms go through the machinery, a stray dead insect falls onto one form and changes the last name to “Buttle,” and the wrong man is arrested. Sam gets involved in multiple ways at the same time. He is first pushed into an unwanted promotion from Records into Information Retrieval (the combination police/interrogation/military/Gestapo) by his mother (Katherine Helmond). Second, he meets the real Archibald “Harry” Tuttle, who operates now as a rogue heating repairman, showing up when Sam’s air conditioning goes on the blink. Tuttle’s interference in Sam’s air conditioning creates its own problem with Central Services and authorized heating repairman Spoor (Bob Hoskins).

The Buttle/Tuttle problems results in a refund check to the Buttles. People are required to pay for their own interrogations and incarcerations, and Buttle was overcharged. The problem is that something needs to be done with the check, and Archibald Buttle was killed in his interrogation, meaning that there is no way to have the check cashed or cleared. Sam agrees to take it to his next of kin, and there he meets Mrs. Buttle’s upstairs neighbor, Jill (Kim Greist). Since she is involved in the Buttle/Tuttle error, she is now wanted as well, and likely to be eliminated as a potential terrorist and troublemaker. She is the woman who appears in Sam’s dream visions; because of this, he gets involved for her sake and risks his entire world to be with her.

Brazil explores a number of themes, including dehumanization for the sake of bureaucracy and illogic posing as logic. The most important, as it incorporates both of those, is the idea of rampant, backwards technology. Gilliam’s world here is full and complete—since nothing happens without the bureaucracy, nothing changes without it. Heating ducts and wiring fill walls, because repairs entail only fixing, not the removal of obsolete technology. Additional pipework and wiring multiply and become less functional and more prone to breaking. Conveniences are specifically inconvenient. A telephone requires multiple plugs to operate, and a simple toaster or coffee maker contains so many moving parts designed to put the toast into a tray or automatically pour the coffee that breakdown is inevitable. The few seconds saved from the additional parts immediately cause problems and reduce efficiency. Nowhere is this better show than the computer monitors, which are tiny. Because they are tiny, each is fitted with a massive magnifying glass, again, a cobbled solution necessary because of red tape rather than the simple logic of creating a larger monitor.

Dehumanization also plays into Sam’s mother’s addiction to plastic surgery under the knife of her doctor (Jim Broadbent). As the film continues, she goes through more and more extreme procedures and gets younger and younger while her friend, under the care of a different doctor specializing in acid, becomes more and more decrepit as her procedures backfire. The idea of rampant dehumanizing bureaucracy also crops up in the character of Jack (Michael Palin), a state-sponsored information retriever (read: torturer), who performs his function while wearing a disturbing mask in the form of a child’s face.

I watched this film originally at a strange time in my life, and my primary reason was because of Gilliam’s Python connection. I was at a strange point in my life in the sense that I knew how the real world worked, but still thought that movies were different. I looked to films as an escape from reality, where a happy ending was assured. Brazil dashed that from my reality, and I can remember being really upset by this film the first (and until now, only) time I watched it. I loved the vision, I loved the visuals, and I understood the point of the end. I got it intellectually, but it hurt me emotionally. But it did move me—years later, I was able to recall entire scenes intact despite more than a decade between viewings.

I’m made of sterner stuff these days. I not only understand the ending on an intellectual level, but I get why Gilliam went in the direction he did. I not only understand it, I appreciate it for what it is. I can even perform the mental gymnastics necessary to give that earlier version of me a happy ending from the emotional gut punch that Gilliam presents. That’s the sign not just of a great film but of something that qualifies as a piece of art. Brazil has presented different meanings to me at different points in my life, and both are equally valid. It’s still not my favorite Gilliam to watch (that’s 12 Monkeys), but I wouldn’t be amiss if I call it his greatest achievement as a director.

——————

Now Vote!

Both of these reviews are excellent and well-structured. It’s really too bad that only one can advance to the next round. These are two of the best that I’ve read throughout the tournament so far. It’s not going to be easy to vote on this one. Nice job to both writers!

Agree with Dan, these are two of the best reviews yet. Went with Kasper because his was just a touch more eloquent, but kudos to both.

I agree as well! Both had a very good feel for a reasonably difficult movie, and wrote very well. Sadly, only one can advance, and I too voted for Kasper.

You should add links to their respective blogs at the end.

Uh, that would kinda kill the whole anonymous thing going on here. We’re not supposed to know who the reviewers are until the competition is over.

Don’t worry, I am.

Dylan: I think he meant at the end of the competition… at least that’s how I read it, which is what I’m gonna do. But if he meant at the end of the post… then, yeah… what you said.

I think I’m actually glad I got distracted and missed this round of voting/commenting. They are both very well written reviews and it’s a shame these two got paired up against each other.