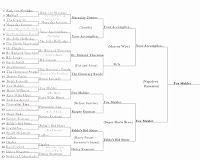

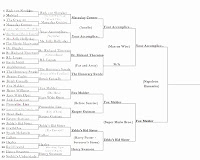

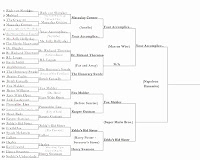

I suppose that’s better than last time, but still really low–especially in comparison to the first two battles of this round (Hell, they’re both low even by Round 1 voting standards). Anyone care to share some thoughts as to why such a drastic decline in votes lately? Anyway, congrats on Fox Mulder for knocking that one out of the park. He’ll be moving on to the next round. Congrats! This battle will see Pinocchio_Liez, who won the first battle of Once Upon A Time In The West, face off against Kasper Gutman, who was considered one of the best reviewers of round 1 with his review of Brazil. So from a movie called Brazil to one that just takes place there, today’s battles are for crime drama, City of God. Read, VOTE, comment, enjoy! You have until Friday. Below is the updated bracket. Click to make it bigger.

—————————

Review #1

By Pinocchio_Liez

American crime movies tend to glorify crime. Films like Oceans 11 portray criminals as people we’d like to hang out with. They’re sort of like Harlequin Romance heroes—they’re attractive, talented, potentially wealthy, and have a whiff of danger about them without really being dangerous. This is true all the way back to the 1930s. While characters like Tom Powers in The Public Enemy are harsh, they’re also charismatic. There’s something attractive about them. People even like psychotic killers. Hannibal Lecter, Freddy Krueger…these guys have fan clubs. Even though we know these are bad guys, there’s a part of us that roots for them at least a little.

Cidade de Deus (City of God) does not present us with this exotic and mildly entertaining life of crime. The people in this film don’t pull off capers or say something droll when polishing off a victim. This is real crime, the sort that we like to pretend doesn’t happen. It’s dirty, ugly and brutal. Violence happens suddenly and without warning, and the cheapest commodity is human life, particularly the lives of children.

The film begins near the end of the tale. Our narrator, Buscape (which translates to “Rocket,” played by Alexandre Rodrigues) is a budding photographer; taking pictures for the newspaper appears to be his one chance out of the slums. As the film begins, a group of gang members are chasing a chicken, which winds up in the middle of the road in front of Buscape. Behind him are the police. Buscape is caught in the middle, and is convinced that the gang wants him dead anyway.

From this point, we spin back in time and into the description of life in the City of God, the most brutal, downtrodden, violent, and dangerous slum in Rio de Janeiro. This starts with The Tender Trio, a gang of criminals who work under the names Shaggy (Jonathan Haagensen), Clipper (Jefechander Suplino) and Goose (Renato de Souza), who is Rocket’s older brother. The three rob trucks and pass much of their profit to the locals, less Robin Hood and more for the guaranteed loyalty against the police. Their scope increases with the idea of Li’l Dice (Douglas Silva), who suggests robbing a brothel. The job goes sour and the Trio breaks up violently.

As it happens the job goes sour because of Li’l Dice, who sees this as an opportunity to start taking over in the City of God. He scares off the Trio, then enters the brothel himself and starts killing everyone he sees, both to get the police after the three criminals and to satisfy his own bloodlust. It should be noted that Li’l Dice is all of eight or nine when this takes place.

Ultimately, Li’l Dice grows up and changes his name to Li’l Ze (Leandro Firmino). He and his cohort Benny (Phellipe Haagensen) take over most of the drug trade in the City of God, leaving only a single other dealer named Carrot (Matheus Nachtergaele) and his reluctant partner Knockout Ned (Seu Jorge). Much of the rest of the film concerns the war between these two rival drug factions—the tense stand-off, the event that triggers the war between them, and the events that escalate this war into a true bloodbath.

Caught in the middle of all of this is Rocket, who is less a participant and more an observer. It’s also fair to say that Rocket is an observer by necessity. As a member of neither gang, his only chance at surviving the brutality of the conflict is by being constantly aware of everything going on around him. By the end of the film, all of these stories and struggles and conflicts have come to a head, with Rocket standing between Li’l Ze’s gang and the police, with Carrot’s gang standing ready to attack. It is this necessity of survival, this instinct drilled into him by so many terrible lessons, that drives Rocket’s decision at the end of the film.

In many ways, Cidade de Deus is the story of a large turf war that encompasses one of the most lawless and terrifying ghettos on the planet. But this is not a story of honor among thieves or soldiers entering conflict. The most salient and repeated feature of this film is that the foot soldiers in this war are children, often of grade school age. This is horrifying stuff. We see a gun slapped into the palm of a 10-year-old forced to choose between shooting one or the other of his younger friends, one of whom is perhaps five. There is no joy or thrill in any of this. There is horror made all the worse because it is so real.

Li’l Ze is one of the most terrifying screen creations in film history. He has no morality beyond taking anything he wants because he wants it, or because he doesn’t want someone else to have it. He is a true monster, a creature of impulse and violence, without any sort of emotion or even a basic humanity. There is nothing in him beyond a desire for destruction and a rapacious greed for power and wealth. Only he exists in his world and everyone else is there to serve him, die for and around him, or be victimized by him. He is all the more terrifying because he is not alone in this mindset; throughout the film there is evidence of the next generation of Li’l Zes coming up in the City of God, just as grasping, just as greedy, just as sociopathic. Even more terrifying is the knowledge that this film is based on a true story.

At its heart, Cidade de Deus is not a new story. It is ultimately the story of an artistic soul (Rocket) caught in a terrible and brutal reality. The only real question is his survival, both physical and spiritual in this crushing world in which he lives. What makes this film special is how simple its story is below the surface complexity of people and grudges and petty rivalries. Fernando Meirelles never loses sight of his narrative despite having to retreat a decade or more to get us back to the starting point and complete the story—noteworthy considering just how convoluted the personalities become. Many characters are lost on the way, but we don’t notice because they’ve become less than tangential to the story. Others, who seem to be minor characters, appear through to the end. But it’s never any more confusing than it has to be, or too difficult to follow.

Its greatest strength, though, is its basic neutrality. It is obvious to any viewer the depths of depravity of Li’l Ze and many of the others, but Rocket never tells us this. The narration is matter-of-fact, judging only the reality of the events and not their greater purpose or meaning. This is left to us to contemplate, and the weight of our own conclusions is what gives this film its undeniable power. While films like Gomorra and Slumdog Millionaire follow in its footsteps, neither of these can match the stark callousness of Cidade de Deus.

—————————-

Now Vote!

I’m not sure how everyone else feels, but it does feel like the tournement is going a bit slow. Maybe if you posted a new round every day (but still kept the voting open for 2 days for each round) it would get more votes?

Anywho..on to the reviews, they were both really great. The 2nd one got a bit long for my taste, so I went with Liez.

I can see that (re: Slowness). It’s because it started with 32 people. Next time I’m gonna cut it down quite a bit. I’m not sure how the new battle every day thing would work. It might overwhelm a lot of people. Hell, I’D be overwhelmed trying to RUN that chaos. But this round barely started and it’s already almost over. And the next round will only last a week. But hey, this was our first time doing this, so we live and learn.

I don’t think shortening the length of time each round is up would result in MORE votes. Sadly, I think the truth is that most LAMBs aren’t interested in things that don’t directly benefit/involve themselves.

Once again we have two very solid reviews, a difficult choice. I voted for Kasper because I like a review that references other films to put it in context.

That’s what I’m afraid of… but here’s the weird part. When we have battles that range in votes from 30-68, but then we get battles that only get in the 20s… it doesn’t make sense.

The only conclusion I can come to, and I’ve actually talked to a few contestants about this already, is that those reviews that get 50+ votes (some of which have some very suspect timing, which I won’t get into here) involve some kind of cheating or telling others to vote specifically for you (which breaks the anonymous rule). This means that there really are only 20-30 people voting, but for a select few people involved… there’s something shifty going on. Now, I *HOPE* that isn’t the case. But it’s really hard to come up with a logical conclusion for why some battles have 60+ votes and others can barely make 20-25.

Kasper by a mile. I found PInocchio’s review really difficult to follow and understand, whereas Kasper’s told me everything I’d want to know about it in clear and concise language. An enjoyable read, if not an enjoyable film to watch.

Both were good reviews once again. I liked Pinocchio’s review as I read it, but I felt that Kaspar put the movie into context much better, if that makes any sense.